Boohoo, bad news. My old tablet being used as an e-reader is no longer compatible with TPL's Libby (Overdrive) system, upgrade impossible. Technology's predisposable junk. Coupled with TPL's slow (but so welcome) recovery from the cyber attack, my reading selection has been limited for a while. A few random finds here.

~ The hunt is on for a Kobo ~

Alice Feeney. Good Bad Girl. USA: Flatiron Books, 2023.

First an unknown woman loses her baby, stolen from her pram in a supermarket. Then we learn that librarian Frankie has lost a runaway teenage daughter. Then we see young Patience, care home worker, who befriends Edith whose daughter Clio barely speaks to her. Clio is a mental health therapist whose new client (Frankie) has not even introduced herself by name yet, when Clio gets word that her mom Edith has run away from her care home. One of these women harbours deep guilt: "I wished my daughter would disappear and now the baby is gone." Mother's Day does not have the same context for everyone.

Frankie goes on an unknown mission to see Clio. Edith hates the care home and made some secret plans. Patience lives in a miserable attic, all she can afford, merely being required to service her landlord once a month or so. Without her mother's knowledge, Clio can no longer afford the care home fees and can't keep up mortgage payments on her house. It's like a bizarre circular dance with changing partners—each deals with a loss that colours her entire life. We are told over and over again that no two people see one person in the same way, with the same lens, yet everyone's truth is true. Did I say there was a murder? ... Patience lands in prison, Clio goes to a cemetery, Frankie frantically searches for her daughter's location.

Police detective Charlotte Chapman is a dark horse. Paper cutting is an art form new to me. Although I didn't care for the way Feeney concluded her Daisy Darker (LL429), this one is absorbing and well told, with her signature fine twists. Good people doing bad things, she reminds us rather often.

Frankie

▪ "I did something terrible, Mum. Something I can't tell anyone else about." (26)

▪ Frankie can feel the woman's eyes creeping all over her. It makes her itch. (60)

▪ "I'm scared, Mum. Please help me." (187)

▪ Frankie had had her fill of people speaking to her as though she were a piece of shit on someone's shoes. (218)

▪ You can't trust anyone, Frankie knows this. People will always let you down in the end, life taught her that lesson when she was young. (256)

Clio

▪ "All you've done for years is criticize me and keep me at arm's length." (32)

▪ The truth, which often hurts more than a lie, is that Clio's mother didn't love her. Didn't like her. Didn't want to know her. (95)

▪ "You tricked her. Got her to sign things she would never have signed if she understood them." (124)

▪ "It's not about the money," he replies and Clio pulls a face. In her experience almost everything is about money in the end. (189)

▪ She's been cast in the role of bad daughter one last time. (241)

Patience

▪ I've lied to Edith Elliot about almost everything since the day we met. (21)

▪ Last week he asked me to do something unthinkable. (113)

▪ "Nobody said anything about murder when I was arrested." (151)

▪ " ... if I'm sharing a cell with you then I've got a right to know whether it's safe for me to close my eyes at night." (180)

▪ "Patient is all I've ever been. That should be my name: Patience." (211)

Edith

▪ "What have you sold? My things?" (30)

▪ "You may as well have put me in prison and left me there to rot (30)

▪ "I didn't need to be the hero in her story, but I grew tired of her treating me like the villain." (99)

▪ "You've been what? Spying on me? Reporting back to him?" (115)

▪ Edith used to visit a church like this one every Sunday until she and God had a falling out. (135)

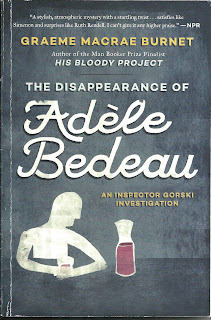

Graeme Macrae Burnet. The Disappearance of Adèle Bedeau. 2014. USA: Arcade Publishing, 2018.

Purportedly written by Frenchman Raymond Brunet and translated by Graeme M. Burnet, the book was actually created by the "translator," quite a literary turnabout, especially for a first novel. The conceit extends to the "translator's" Afterword, where he additionally creates an entire life and career for false author Brunet.

In traditional French police procedural vein, it sounded more exciting than first getting into it. An attractive young waitress in a popular town restaurant goes missing. No one saw her after her last evening shift, or admits to having seen her. Regular customer Manfred Baumann actually did see her meeting a young man at a park and riding off with him on his motorcycle. Why did Manfred not say that to investigating detective Georges Gorski? A digression into Manfred's history explains his hesitation in front of police and his general diffidence with women (without giving away a key element here). As for Gorski, he too deserves biographical background details.

Eventually the young man comes forward to tell Gorski he lost track of Adèle during their drunk date, but that on one occasion he'd seen Manfred speaking to her by the park. Manfred is an outlier, a creature of habit, works at a bank, eats his meals locally. Once a week or so he frequents "Madame" Simone's bar in nearby Strasbourg, to hire a sex worker for a half hour; with regular women he is shy. Prone to overthinking in most aspects of his life, he is socially awkward and self-conscious to an extreme. One momentary lapse in not answering Gorsky truthfully leads to full-blown unintended consequences. Manfred comes to believe that everyone regards him with suspicion—is he the prime, the only, suspect in Adèle's disappearance?

Dry is the initial impression—no red herrings here, no intricate plotting, but not without humour. It took a bit of time for me but the deep psychological / character study grew compelling. Small town life and personalities ring authentically. Altogether, executed with quietly expert panache. (Burnet's second novel, His Bloody Project, was shortlisted for the Mann Booker Prize 2016.)

Manfred

▪ Manfred clasped his hands and set them on the table in front of him in an attempt to stop fidgeting. He did not feel he was making a good impression. (31)

▪ From now on he must avoid attracting attention to himself. He must not give people cause to think that he had been behaving oddly. (46)

▪ He intensely disliked the idea that Gorski had been asking about him, asking everyone about him. (51)

▪ "So, Monsieur Baumann, what's this I hear about a young lady in your life?" (128)

▪ Did he not, after all, already live his life as if he was constantly being watched, as if he expected at any moment to be challenged to explain his actions or to answer charges unknown? (140)

Gorski

▪ It was not even clear whether a crime had been committed. (57)

▪ It was all speculation and Gorski did not like speculation. He liked to proceed with solid, logical steps based on concrete evidence. (61)

▪ "You have consistently lied about seeing Mlle Bedeau on the two nights in question, leading me to conclude that there is something in your relationship with her that you wish to conceal." (137-8)

▪ Since their marriage, Céline had been relentless in her intolerance of Gorski's lower class mannerisms, endlessly correcting his speech and reprimanding him for wiping his mouth with the back of his hand or holding his cutlery incorrectly. (164)

▪ On paper, Baumann was a compelling suspect. (202)

No comments:

Post a Comment